He stood in the corner of San Francisco’s Department of Motor Vehicles, clutching the handles of his walker and waiting for his turn to apply for an identification card. He’d lost it a few years ago, along with his home, his health and his dignity.

“I recognize those two people right there,” he whispered to me, anxiously, nodding at a man with a long braid and a young woman in a blue dress just feet away.

Ben Campofreda, 41, had smoked fentanyl many times with the pair on the sidewalks of the Tenderloin. He hoped they wouldn’t spot him.

After lifesaving surgeries and a hospital detox, he could stand instead of slumping in his old wheelchair. His long hair, once grimy, was cut short. He wore clean clothes.

Ben had been sober for four months by that September afternoon and aimed to keep it that way. Reconnecting with anyone from his old life, he figured, could jeopardize that. Fortunately, his former friends took no notice of him.

“I love that nobody recognizes me,” he said. “There’s a rumor on the streets that I died on the operating table. I told my dad about that, and he said, ‘Good. Let everybody think that you’re dead.’”

The rumor may be more believable than the truth — Ben had managed to kick fentanyl, the terribly powerful and addictive opioid that has radically changed San Francisco. He told me that of all the friends he made smoking “fetty” on city streets, 40 had overdosed and died. Just one, he said, is in recovery.

I’ve been following Ben since late August because his story exemplifies so much about the cruelty of a city that makes it far easier to buy deadly drugs than to access treatment to leave them behind. But his journey shows there’s hope for the legions of people like him dotting the Tenderloin and South of Market districts in a fentanyl-fueled fugue, often sprawled on the sidewalks or folded over where they stand.

With the help of family and friends, talented health care workers and the resolute determination to be free of addiction, a better life is possible. But the obstacles are significant. The question as I kept in touch with Ben was whether he could hold on to his new sobriety and avoid falling back into the chaos of life on the drug.

In the DMV, the numbers ticked.

“Lucky 13!” Ben said. “I’m next! All right, I’m ready.”

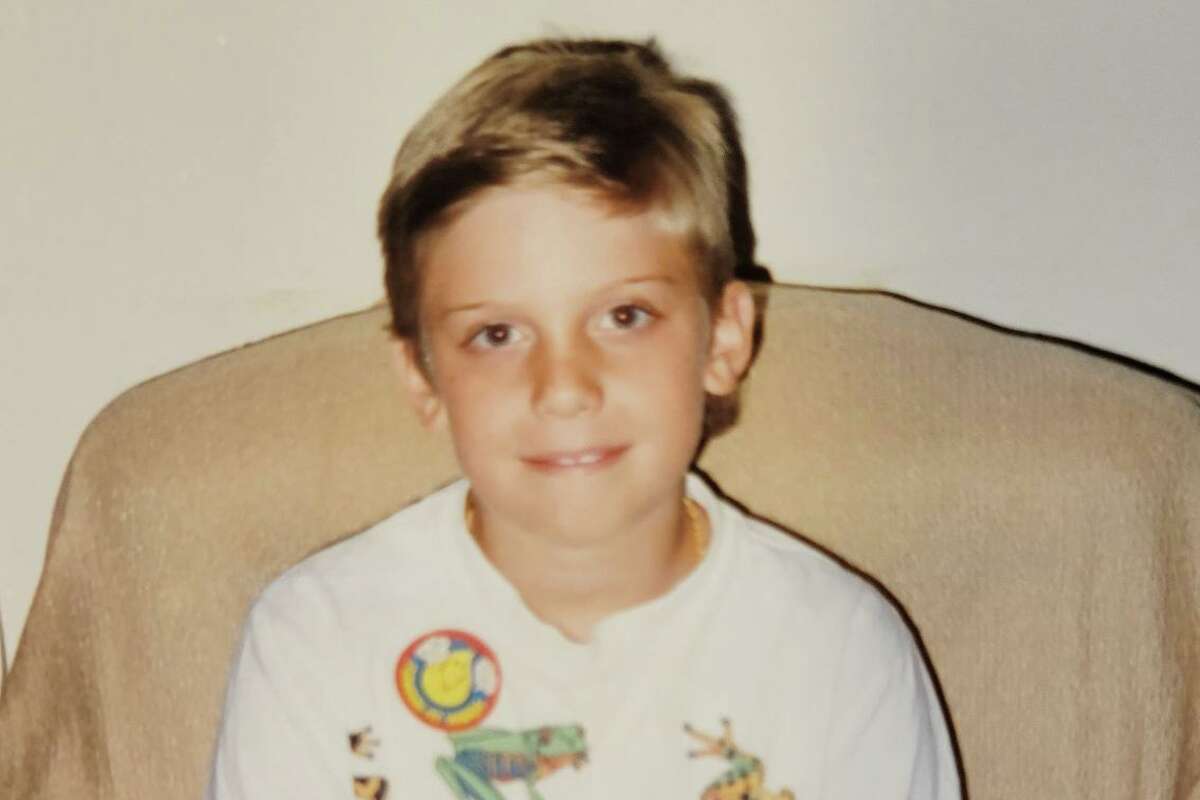

Ben Campofreda, about age 7, at his grandparents’ house in Virginia

Courtesy Judi Johnson

Ben Campofreda, in his early 20s, at a restaurant celebrating his great-grandmother Mary’s birthday.

Courtesy Judi Johnson

Top: Ben Campofreda, about age 7, at his grandparents’ house in Virginia. Above: Campofreda, in his early 20s, at a restaurant celebrating his great-grandmother Mary’s birthday. Photos provided by Judi Johnson. At top of story: Campofreda walks through San Francisco’s South of Market neighborhood to catch a bus to his drug treatment program.

Ben, who grew up in Virginia, developed spinal stenosis as a teenager; a lack of space in the backbone puts pressure on nerves in his spine. By 20, he had constant, extreme back pain.

A doctor prescribed Oxycodone, and Ben loved both the relief from his pain and the energy the pills gave him. Within a couple years, he’d developed a serious addiction, consuming an entire month’s supply of 120 pills in a day by crushing and snorting them. He found an M.D. who would write prescriptions for more for $100 a pop and supplemented all that by buying pills on the street.

This allowed him to live a successful life as a snowboarding instructor in Colorado, then as a sound engineer and production manager who toured with musicians including the rapper Macklemore.

But the addiction grew stronger, and buying all those pills was expensive. In his early thirties, Ben switched to heroin, which was cheaper.

He moved to Santa Clara with a girlfriend six years ago to be near her family, working remotely for a Colorado company that provides online courses to educate people about cannabis, including how to run successful dispensaries and how to cook with it. He tried to hide his worsening dependence on opioids from his girlfriend, but she was suspicious of his increasingly strange behavior and dumped him after catching him smoking heroin on a camping trip.

His boss fired him too after Ben was high and incoherent during a weed conference in Seattle.

Next came a stint in an RV that he parked in Millbrae, providing an easy starting point for Uber rides into the city to buy heroin. When his RV broke down and was impounded, he couldn’t afford to get it out. So he settled into life on the streets of the Tenderloin, never calling one corner home, but just wandering.

Almost immediately, someone stole his backpack with his wallet and phone. And finally he did what so many have done: He switched to fentanyl, which was cheaper than heroin and far stronger.

He funded his addiction by dumpster-diving, explaining to me that many San Franciscans are so rich that they throw away clothes with tags on them, sunglasses, electronics and toys. He sold whatever items he could salvage by spreading them on a tarp or a blanket at Sixth and Market streets at night.

He often ate breakfast, used the bathroom and got toiletries at Glide Memorial Church or St. Anthony’s and got more goods from outreach workers.

“There was a lot of food offered,” he said. “People would hand out tents and sleeping bags, toothbrushes, deodorant, harm-reduction supplies. They would give out meth pipes, crack pipes, aluminum foil.”

The drugs were the easiest to score of all — dealers were everywhere, and fentanyl was dirt-cheap — and soon his life was entirely centered around scoring his next hit.

“The dealers figured out the science of that one real good,” he said of fentanyl. “It’s a jackpot for them. You constantly need it, you constantly want it and you’ll do anything you can to get it.”

A cop, every so often, would approach him in the Tenderloin and tell him to put his drugs away. He doesn’t recall a single outreach worker offering him treatment on the street, even as the city’s drug crisis grew so severe that one or two people, on average, died of overdoses every day.

He rarely slept at night, using methamphetamines to stay awake, and sometimes stretched out on a pew at St. Boniface Church to doze during the day.

“Everywhere else,” he said, “you’ll just get robbed.”

He managed to get by OK for a while, but then an infection in his legs made its way into his spine, and he couldn’t walk. He became confined to a wheelchair, unable to use the bathroom or get food without help. He normally weighed 170 pounds, but as his health grew worse, he shrunk to a startling 100 pounds. His hands grew red and puffy, a common symptom of opioid use.

“I wasn’t taking care of myself at all,” Ben said. “I didn’t know what was wrong with me.”

Campofreda on the streets of San Francisco shortly before his friend took him to UCSF in the spring for medical help and to beat his addiction.

Courtesy James NugentOne thousand two hundred and seventy four. By the count of Judi Johnson, that’s the number of days her son was homeless.

“San Francisco reminds me of a Mad Max movie,” she said. “It’s beautiful and the weather’s nice, but I don’t understand how you can let people do drugs on the street like that. It’s not compassion. It didn’t seem like there was any help.”

She flew to the city from Virginia four times to visit Ben and was shocked by his worsening health. The skinny, filthy man in the wheelchair looked nothing like her little boy.

“He was gaunt. He was sick. He was off-color. He had sores,” she said, crying at the memory. “It just broke me. It still hurts to think about it.”

She found him easily each time just by walking around, then offered him help like food, hotel stays and phones he kept losing.

“I never went there thinking I could change him,” she said. “I just hoped Ben would see how much I loved him and come back.”

He didn’t, and when the pandemic struck, she stopped flying out west. She worried about her son during the day and dreamed of him at night, joining a growing number of parents whose children are addicted, homeless and lost here.

“San Francisco reminds me of a Mad Max movie.”

— Judi Johnson

Allison Lawler, 33, Googled her old college boyfriend on Valentine’s Day of this year on a whim. She found Ben’s name and photo in an online essay about San Francisco’s homeless people and their pets. Shocked, she flew south from Oregon.

Arriving one weekend in March, she found her once-vibrant and athletic companion sitting in his own waste in a wheelchair in United Nations Plaza, his back wrecked, his skeletal body nearly folded in half. He was, she recalled, “continuously smoking drugs and having uncontrollable twitches.”

Mayor London Breed had by then opened the Tenderloin Center in the plaza, with a goal of linking the city’s most vulnerable people to housing and treatment, but Lawler learned that it offered no assistance on weekends.

She initially booked a room at the Phoenix Hotel in the Tenderloin, planning to clean Ben up and accompany him to the center that Monday. But after she realized her friend had open, feces-infected sores on his legs, she called 911 against his wishes.

She urged the paramedics who arrived to place him under an involuntary psychiatric hold. They said they couldn’t. One, Lawler said, suggested she wait until Ben fell unconscious from the infection in his legs, then call 911 again. That made no sense to her.

“It’s a slow suicide, right?” she said. “Who are we protecting by letting someone die on the streets?”

Lawler returned in April on a weekday to visit the Tenderloin Center. She said she spent a frustrating day there with Ben, who smoked fentanyl in an outdoor area. (The practice was allowed and may have saved lives, with workers able to administer the antidote Narcan to those who overdosed.)

While the staff was kind, she said, the programs didn’t seem coordinated, and finding housing for someone in a wheelchair seemed particularly difficult. After many hours, staff members gave Campofreda a spot at the Cova Hotel on Ellis Street. But the bathroom wasn’t big enough for his wheelchair and he didn’t stay. Lawler went home again, defeated.

In the nearly 11 months it was open, people made about 123,000 visits to the Tenderloin Center, where basics like food and laundry were plentiful. Center staff members reported making 1,500 connections to housing or shelter, but there were only 397 “linkages” to mental health or substance abuse services.

Whether those referrals were successful is unclear. The city didn’t measure outcomes, a lost opportunity to help more people like Ben recover.

Breed had pitched the center as a conduit to longer-term care. By that measure, it failed. And rather than work to improve it, Breed this month shuttered it with nothing new to take its place for the more than 7,700 people in the city who are homeless and the untold number who are struggling with addiction.

I wanted to ask the mayor about the closure of the Tenderloin Center and whether she considers the city’s treatment system effective, but multiple requests for interviews with her over three weeks were not granted.

James Nugent, one of Ben’s best friends, was trying to find him, too, calling police, homeless aid groups and even the city morgue.

His breakthrough came after contacting Miracle Messages, a nonprofit that aims to reconnect unhoused people with their families. Soon after Nugent called, one of the group’s volunteer detectives, Liz Breuilly, called him back and agreed to search for Ben, finding him quickly.

Nugent flew in from Washington, D.C., in May, met Breuilly and then found his friend smoking fentanyl in United Nations Plaza, his head covered by a dirty jacket.

“He’d hit his drugs and then all of a sudden would be in la-la land for 45 minutes to an hour and then do it again,” Nugent said.

When some addicts fell unconscious, he noticed, dealers stole their belongings. Police officers were scarce. Meanwhile, office workers strolled through the plaza carrying bags of Whole Foods groceries, ignoring the scene around them.

“It looked like a war zone,” Nugent said. “And no one was doing anything about it.”

At one point, Ben asked Nugent to lift one of his legs onto the footrest of the wheelchair because it was dragging on the ground, and he couldn’t raise it. Nugent felt warm liquid. “He was actually peeing on me,” he said.

That was it. He told his friend he was going home and wouldn’t visit again. “I said, ‘I don’t want to remember you like this. I want to remember the good times.’ I think that hit him hard.”

Nugent left for his hotel, but soon received a call from Breuilly. Ben had called her to say he was finally ready to get help.

When they met at 9 the next morning, Breuilly told Nugent to take Ben to UCSF Medical Center, where he would have a better chance at obtaining long-term, intense help than at the smaller hospitals nearer the Tenderloin.

After arriving at UCSF, Nugent and Ben said, medical staff removed Ben’s soiled pants. Maggots fell out of the sores on his legs. Doctors later told Nugent that Ben, if he remained outside the hospital, would have died within a week.

That was May 15. It was the last day Ben used fentanyl or any other illicit drug, he told me. He marks May 16 as his sober date — the day he began to come back to life.

Ben arrived at UCSF Medical Center with osteomyelitis and discitis, severe bacterial infections in his lower back. The infections had eroded his two lowest vertebrae and spread to his tailbone. He was extremely skinny and, in the words of Dr. Alekos Theologis, a UCSF orthopedic surgeon, “depleted of all nutrition.”

“People who are addicted to drugs and who are malnourished and who have a compromised immune system are prone to these infections,” he told me.

What came next, Theologis said, was “miraculous.”

The treatment by a team of surgeons, doctors, nurses, nutritionists, social workers and others began with a complicated surgery to remove bone that was pressing on the nerves in Ben’s back. A second surgery included cutting out the infection and using a metal cage to reconstruct his spine.

Over the summer in the hospital, Ben began to recover the use of his legs. He gained more than 50 pounds. “Even though his recovery was slow, I must say that it was dramatic,” Theologis said.

The team gave him the anesthetic drug ketamine to ease his withdrawal and later prescribed him methadone for the same purpose upon discharge.

Ben, who is on Medi-Cal and paid nothing for his stay, said someone in the hospital told him his care cost more than $1 million. Theologis said he didn’t know the exact figure, but that the estimate “was very possible.”

Dr. Daniel Ciccarone, a UCSF professor of addiction medicine who didn’t work on Ben’s case, called Ben’s transformation “a welcome miracle.” He said he doesn’t know how many people like Ben recover from fentanyl addiction, but called it “unfortunately low.”

“Even though his recovery was slow, I must say that it was dramatic.”

— Dr. Alekos Theologis

Fentanyl is highly potent and addictive. Treatment slots are too few. The federal government heavily regulates methadone to treat it, limiting its availability and requiring frequent trips to licensed opioid treatment facilities to access small quantities. Another drug, buprenorphine, isn’t effective until after a few days of painful withdrawal, Ciccarone said, noting that many patients give up in the meantime.

“You have to be lucky and persistent and know people and be motivated and be ready to go through all the hard work that it means to go through recovery all at the same time,” he said. “People do it, and I find it utterly remarkable and extraordinary.”

Ben, his family and his friends praised the hospital for devoting so much time and effort to him. But at his discharge in August, the city’s lack of a coherent treatment system became clear.

Ben needed to stay nearby for follow-up appointments, but UCSF social workers could not find a good place for him to go.

They recommended a medical respite facility at Eighth and Mission streets. But the corner teemed with drug dealers, and Ben said he had a panic attack when told that was his best option. The only other place the social worker could find, he said, was a medical respite facility in Oakland.

Ben went there with a prescribed stash of painkillers for his back and methadone to curb his cravings, expecting someone would keep it for him and dole it out in small quantities. Nobody did. He stayed alone in a room with piles of drugs, frantically trying to find a program that fit his needs.

In late August, Breuilly, the Miracle Messages detective, reached out to me. She’d been phoning her contacts, asking where someone who had three months of sobriety and no home could go. She couldn’t find anything.

Ben Campofreda, a recovering fentanyl addict, walks back from the pharmacy in Oakland, Calif., on Friday, Sept. 2, 2022. He is recovering from multiple surgeries in a respite in Oakland before seeking drug treatment.

Gabrielle Lurie / The Chronicle“I’m so desperate to help him, I could just scream,” she told me in one of our conversations. “He is scared to death. He doesn’t leave his room.”

Ben and I started chatting, and he provided regular updates. He said he left “dozens” of messages at city agencies and treatment centers, but either didn’t get calls back or received contradictory information.

“It’s been a lot harder than I planned,” he said. “They keep asking me if I have a case worker, but they can’t tell me how to find one.”

A UCSF social worker suggested he visit the Tenderloin Center — and he did, wearing a ball cap, sunglasses and COVID face mask as a disguise in hopes of avoiding his old friends.

He’d visited the center about a dozen times before, but only to smoke fentanyl and meth in the back, lured by free meth pipes and the ease of bumming drugs off fellow users. He said San Francisco should create overdose-prevention sites, but also drug-free places to seek treatment.

“I was literally looking out a window watching someone use while I’m trying to find rehab and trying to stay sober,” he said.

“I’m so desperate to help him, I could just scream.”

— Liz Breuilly, Miracle Messages volunteer

Ben said he visited the center five times in the fall, but it never led to much help. Once, after being assessed for housing, he said he was told he didn’t qualify. Another time, he said a staffer recommended visiting the office of HealthRight360, a treatment program, “to introduce himself.”

He said a staffer at HealthRight360 asked why he was there since he was already sober. “I’d like to stay that way,” he responded. He said he was told it was too late in the day to enter the nonprofit group’s detox program, but that he could come back the next day and try again.

UCSF provided car rides from Oakland, but needed several days of advance notice. Ben said he wanted to make sure HealthRight360 could place him immediately if he went back. He said he called the nonprofit and left messages that weren’t returned.

He grew increasingly frantic. He knew his recovery was fragile.

Ben should have been able to get treatment at any hour of any day. San Francisco voters in 2008 passed a measure mandating it. But 14 years later, the city is far from reaching it.

At a recent Board of Supervisors hearing, officials with the Department of Public Health were adamant that San Francisco offers treatment on demand, but advocates say that’s not true.

San Francisco has no nighttime or weekend options for seeking treatment, makes little effort to proactively educate people addicted to drugs about treatment options, and offers no navigators to help people figure out the bureaucratic treatment system once they’re ready. For people like Ben, who are already on the edge, the system needs to be a lot more supportive. Any delay or confusion can be devastating.

Department of Public Health officials said in a statement that 4,544 people received drug treatment — including methadone to curb cravings, outpatient treatment and residential treatment — through its programs in 2021. The wait time for methadone programs is less than one day, and the wait time for 90-day residential drug treatment is four days, they said.

The department said people seeking treatment should visit the Behavioral Health Access Center at 1380 Howard St., from 8 a.m. to 7 p.m. on weekdays, or call the center 24 hours a day at 415-255-3737.

I called the number recently and, as a test, asked how someone can get treatment for a fentanyl addiction.

The call-taker said to visit the Howard Street center, but noted it was open for intake only from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. on weekdays and was closed for two hours Wednesday afternoons. He said detox was usually available quickly, but that securing outpatient or residential treatment could take up to two weeks.

Critics of the city’s system say people addicted to drugs often hit rock bottom at night or on weekends and that if they can’t get immediate help, they may seek fentanyl.

I described Ben’s plight to Dr. Hillary Kunins, the city’s behavioral health director. “It’s important feedback for us to receive, and we want to make sure people know how to get help,” she said, noting she intends to expand the hours for the Howard Street facility.

She said outreach teams do “motivational interviewing” in which they ask addicts what they need but also urge them to change their behavior.

But Sara Shortt, co-chair of the Treatment on Demand Coalition, an advocacy group, said the city needs to improve its treatment services and ensure that people addicted to drugs know about them and can access them.

“Much more public education needs to be put out there, and in some cases, people really need more navigators or case managers or people who are going to hold their hand through the process,” she said. “All of that is nonexistent for the most part.”

San Francisco has a new advocate for people like Ben in Supervisor Matt Dorsey, who’s in recovery himself after years of alcohol and crystal meth addiction. He smartly wants to task police with keeping dealers away from blocks with treatment facilities. He wants treatment intake available 24/7, a 311-like call center for people seeking help and a response team available to pick them up within an hour and help them navigate the process.

He said he recently helped a friend addicted to crystal meth access treatment, a process he found frustrating and confusing.

“This is never going to be the issue of the month for me,” he said. “I consider it the obligation of my survival.”

Ben made a Sept. 22 morning appointment at HealthRight360, and I asked permission to attend. That’s when things finally clicked. They told him he could move into a treatment facility on the edge of Buena Vista Park that day.

“That’s awesome!” Ben said. “I’m stoked.”

Getting into detox can happen quickly if someone shows up by 3 p.m., said Vitka Eisen, executive director of the nonprofit. But she acknowledged that a city that truly offered treatment on demand would have it available all day, every day and would be more explicit about how to get the help. She said a staffing shortage has made offering immediate treatment even more challenging.

I visited Ben at the Buena Vista Park facility the following week, and he seemed calm and happy. He described attending morning meetings in the chapel and walking in circles around the large room in the afternoon for exercise. He attended online Narcotics Anonymous meetings and had been connected to a doctor, a psychiatrist and a dentist to pull meth-rotted teeth.

“It’s been really great here,” he said. “The program is awesome now that I’m in it.”

After a couple of weeks, he moved to a longer-term treatment facility on Hayes Street. Now, he can go for walks outside. All participants must perform jobs; he folds laundry.

He talks to his parents every day, and numerous friends have visited. He voted on Election Day and celebrated Thanksgiving at the facility with turkey and stuffing. He’s recording a podcast called “Rehab Undercover.” Perhaps most stunningly, he no longer needs his walker and can walk and climb stairs with ease.

Ben Campofreda is dropped off at HealthRIGHT 360 in San Francisco, Calif., Thursday, Sept. 22, 2022. Campofreda began his 90 day-residential treatment in his attempt to stop his fentanyl addiction.

Santiago Mejia/The Chronicle

Ben Campofreda arrives at HealthRIGHT 360 in San Francisco, Calif., Thursday, Sept. 22, 2022. Campofreda began his 90 day-residential treatment in his attempt to stop his fentanyl addiction. He sits in an office to process his paperwork before going to the treatment center.

Santiago Mejia / The Chronicle

Top: Ben Campofreda is dropped off at HealthRIGHT 360 in San Francisco on Sept. 22. Above: He sits in an office to process his paperwork before being admitted to the treatment center. Photos by Santiago Mejia/The Chronicle

Campofreda walks through HealthRight360’s Walden House in San Francisco, where he was undergoing his drug rehabilitation.

Gabrielle Lurie / The Chronicle

Ben Campofreda, a recovering fentanyl addict, shows off his bracelet reading â Every Day Countsâ while in his room in rehab at Walden House in San Francisco, Calif., on Saturday, Nov. 6, 2022. He is recovering from multiple surgeries while getting drug treatment.

Gabrielle Lurie/The Chronicle

Ben Campofreda, a recovering fentanyl addict, (right) meets with his therapist to discuss his progress in San Francisco, Calif., on Friday, Oct. 7, 2022. He is recovering from multiple surgeries while getting drug treatment.

Gabrielle Lurie / The Chronicle

Ben Campofreda, a recovering fentanyl addict, organizes a piece of laundry at his drug rehabilitation program at Walden House where hopeful messages are on the walls in San Francisco, Calif., on Saturday, Nov. 6, 2022. He is recovering from multiple surgeries while getting drug treatment.

Gabrielle Lurie / The Chronicle

Top: Ben Campofreda shows off his bracelet reading “ Every Day Counts.” Middle: He meets with his therapist to discuss his progress. Above: Campofreda does laundry at his drug rehabilitation program at Walden House in San Francisco. Photos by Gabrielle Lurie/The Chronicle

Ben Campofreda organizes chairs in a meeting room at Walden House’s 30-day detox center in San Francisco.

Gabrielle Lurie / The ChronicleHe plans to enter a HealthRight360 step-down facility where he’ll be able to live for a year or two while getting help seeking a job. He hopes to become a drug counselor.

Dec. 16 marks his seven-month-sober date. His mom and friends still can’t believe their happy, healthy guy is back. A miracle, his mom calls it. Like winning the lottery, his ex-girlfriend said. As good an outcome as one could have possibly hoped, his surgeon told me.

He goes back to his old stomping grounds for methadone appointments and no longer worries about getting recognized by his old friends.

“I hope that when people see me out there and see what I’m doing, it can maybe be a glimmer of hope for them,” he said.

And he no longer worries much about succumbing to the lure of fentanyl.

“Actually, it’s the complete opposite,” he said. “I can’t believe that s— had such a crazy hold on me. It’s like being held hostage.”

But now, at last, he’s free.

Heather Knight is a San Francisco Chronicle columnist. Email: [email protected] Twitter: @hknightsf

Campofreda greets a friend he had used drugs with on the streets after a therapy session in San Francisco.

Gabrielle Lurie / The Chronicle