Professor says the B.C. provincial government is censoring him

Article content

Editor’s note: This column has been updated with a response from the British Columbia Centre on Substance Use.

Advertisement 2

Article content

One of Canada’s leading experts on drug addiction says British Columbia’s provincial government asked him to delete a crucial database in an attempt to censor criticism of the province’s homeless policies. The incident appears to fit within a larger, nationwide campaign to silence experts who believe that, when it comes to homelessness and drugs, Canadian policy-makers are on the wrong track.

Article content

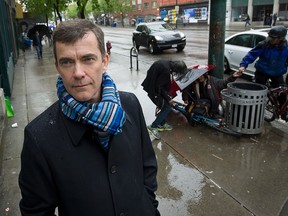

Dr. Julian Somers is a clinical psychologist and distinguished professor at Simon Fraser University, where he directs the Centre for Applied Research in Mental Health and Addiction.

In 2004, Somers established the “Inter-Ministry Evaluation Database” (IMED), which linked data about vulnerable populations across various B.C. ministries — for example: days spent in hospital, detentions and criminal convictions, medications, and income assistance. This helped create detailed pictures of people’s lives, allowing researchers to more accurately measure the impacts of government policies.

Advertisement 3

Article content

Over the years, the database was used in over 30 provincial reports, 60 peer-reviewed publications and several graduate theses.

Somers then used the IMED for his own $20-million research project into anti-poverty programs in Vancouver. The project randomly divided 497 participants into three groups, giving each a different support program. Using the IMED to follow their lives over five years, it concluded that B.C.’s standard approach to homelessness was ineffective.

-

Adam Zivo: Canadians see what governments and activists won’t admit — homeless crime is a real threat

-

Adam Zivo: Encampment activists callously harass victims of street crime

In B.C., as in much of Canada, the popular approach is to herd homeless people into housing where most, if not all, residents are fresh off the streets, creating a critical mass of trauma and addiction. These residents are then given a “safe supply” of free drugs and provided few resources for recovery and social reintegration.

Advertisement 4

Article content

Somers’ study showed that if you house homeless people in a way that disperses them into normal society, and then prioritize rehabilitation, employment and social reintegration, you see a 70 per cent reduction in crimes committed and a 50 per cent reduction in medical emergencies, all without spending more money.

The study confirmed the common-sense notion that it’s better to empower people to get back on their feet, rather than foster dependency through easy access to free drugs.

In a phone call, Somers contrasted Canada’s approach to that of Portugal. The Portuguese are legendary for effectively tackling addiction while decriminalizing drugs, but many don’t realize that their model focuses heavily on rehabilitation.

Advertisement 5

Article content

The Portugal model model focuses heavily on rehabilitation

“Portugal has 64 therapeutic communities and zero consumption sites. British Columbia has zero therapeutic communities and 40-something consumption sites,” he noted.

Armed with his study results, Somers worked with 14 non-profits to call for reforms to B.C.’s drug and homeless policies. In late February 2021, he presented his findings to several provincial deputy ministers.

A week later, the provincial government sent him a letter demanding that he destroy the IMED within one week. The official explanation was that the database was set to be retired at the end of the month, and that the government was creating its own inter-ministry database that would be broader (i.e. include family and income data) and be more efficient to operate.

Advertisement 6

Article content

Somers found the explanation implausible, and still does.

He says there was no way to reconstruct the IMED’s core data in the new government project. Many people had consented to having their data used only because they participated in projects specifically related to the IMED, such as Somer’s aforementioned homeless study. That consent was non-transferrable.

The abrupt timing also troubled him, especially because the B.C. Ministry of Health had just renewed its commitment to the IMED for another year.

The abrupt timing troubled him

Somers refused to comply. He alleges that the government responded by simply prohibiting him from updating or analyzing the IMED, or using it for new projects, without the province’s written permission. Dr. Somers says this effectively rendered the database worthless.

Advertisement 7

Article content

Somers believes that in the nearly two years since, he has been “completely frozen out” by the B.C. government. “This government is actively hostile to the existence of the data, so I’ve completely given up. The work I was doing is no longer viable,” he says.

Somers also alleges that he has been subject to an intimidation campaign by safe supply advocates. He provided a copy of a July 2022 email from the British Columbia Centre on Substance Use, which lobbies for safe supply, showing that they lobbied for a conference to disinvite him from speaking at an academic conference. A BCCSU spokesman said, by email, that the organization raised concerns about what it viewed as the “low quality” of Somers’ research. “There was no request to disinvite the presenter,” the spokesman wrote.

Advertisement 8

Article content

However, the email to the conference organizers from BCCSU expressed hope that “this work will not be given a credible platform.”

When emailed about Dr. Somer’s allegations, the Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General, which had requested the IMED’s deletion, replied that the deletion request “coincided with the expiration of relevant information sharing agreements between Dr. Somers and the Ministries,” and alluded to the superiority of the provincial government’s new, in-house database.

The Ministry also said that, in January 2022, Dr. Somers was informed that he could have continued access to the IMED until March 2023 to allow “existing projects to conclude” and “select” published findings to be replicated in the new government database.

Advertisement 9

Article content

The Ministry did not respond to my question concerning why the initial IMED deletion request was done so abruptly. The Ministry also did not respond to a direct question about Dr. Somer’s accusation of being “frozen out” of governmental communication, nor did it explain why, ten months after first ordering the deletion of all IMED data, it changed its mind and allowed Dr. Somers conditional access to the database.

Other public health and addiction experts say they are unsurprised at the suggestion that there is political pressure being placed on researchers whose findings are inconvenient for governments.

Dr. Kelly Anthony, a lecturer at the University of Waterloo’s School of Public Health Sciences, called the B.C. government’s abrupt request to delete the IMED “concerning, considering the deeply politicized nature of Dr. Somers’ work.”

Advertisement 10

Article content

She also said she wouldn’t be surprised if Somers was being punished for criticizing the government’s commitment to “safe supply.” Anthony believes safe supply is poorly researched and “consigns the addict to be a slave forever,” but says that in her experience, many academics are uncomfortable publicly criticizing it due to silencing, shunning and political pressure.

This sentiment was echoed by Dr. Vincent Lam, the medical director of Coderix Medical Clinic, an addictions clinic in downtown Toronto. Lam is not familiar with the specifics of Somers work but he has publicly criticized safe supply as irresponsible. He told me that at least 10 of his colleagues have privately messaged him to express similar concerns about the potential harms of flooding communities with free opioids. He said they all, too, shared their discomfort with speaking up in a politicized environment where experts are punished if they ask the wrong questions.

National Post